Uh, what’s a Magic Harp? Is that a harp that will magically make me an awesome player?

Not quite – though we can all wish! Back in 1993, two harmonica players from Massachusetts patented a system of harmonica note layouts (or tunings) that they called “Magic Harps.” All the note layouts have three things in common:

- In every hole, the draw note is always higher in pitch than the blow note (unlike standard tuning on diatonic harmonicas where, starting in Hole 7, the blow note is higher than the draw note).

- The tuning layout repeats, instead of changing every octave the way it does on a standard diatonic. In some Magic Harps, the layout repeats every octave. In the one I’m featuring in this post, it occurs only twice over a span of nearly four octave, but it does repeat.

- Every Magic Harp tuning gives a unique combination of chords, by design and not as an afterthought.

The inventors were Pierre Beauregard (founder of the Cambridge Harmonica Orchestra) and Richard Salwitz (aka Magic Dick of J. Geils and Whammer Jammer fame). They aimed to have the Magic Harps commercially produced, but that didn’t happen, and the few Magic Harps out there were built by custom harp builders.

In early November of 2018, I came into possession of five Magic Harps, all built for a single customer by customizer Jimmy Gordon. They had been offered for sale on eBay and were acquired by Jason Ricci. When I arrived at the Harmonica Collective teaching event in New Orleans a few days later, Jason handed them to me and said, “Here, figure out how these are tuned and let’s sell them.”

I figured the tunings out pretty quickly, and later, when I was back home in San Francisco, I sold four of the harps via Facebook Live posts where I played the harps and explained their note layouts. (At the bottom of this page I give links to the videos where I explain and demonstrate each tuning.)

But I kept the most unusual Magic Harp for myself. It was a nailed-together Marine Band with a wood comb that was musty from what seemed to be mildew, and one of the reeds was cracked, but that wasn’t why I kept it. I held on to it because I love the unusual chords it produces. (I’ve since replaced the comb with a linen Blue Moon comb that approximates the original appearance, and am working on replacing the bad reed, though it’s hard to match the reed size with the required pitch.)

Now, give an alternate-tuned harp to most harp players, and they’ll look for what notes bend, what scales it plays, and what cool licks they can play.

I go in the opposite direction, Sure, I check out all that stuff, but the first thing I do is check out what chords the harp will play. And sometimes, even though a harp is designed to give a particular set of individual notes, it ends up plays some really unusual and cool chords.

The chords that this harp produces include one major chord and one minor chord, but with extension notes above and below the chord notes that make for some unusual and beautiful sounds. I’ll go into details later, but first, why not simply experience what this harp sounds like via two recordings I made with it?

Hearing this harp played in C major

The harp was built to play the scale of C major pentatonic (a five-note scale), and I composed and recorded the tune Soulagement to mainly use that scale, though I added some non-scale notes with bends and overblows.

Hearing this harp played in A minor

Later, I had a long phone conversation with Magic Harp designer Pierre Beauregard, who encouraged me to also try playing it in A minor pentatonic, which uses the same notes as C major pentatonic, but with A as the tonal center. Instead of a composed and arranged piece, this time I simply hit “record” and improvised this piece called Blue Quartz:

Why this note layout?

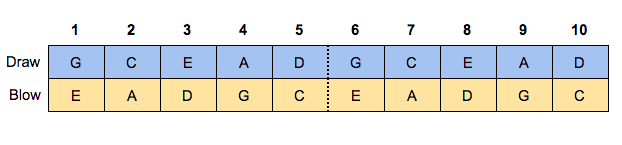

Here’s the note layout for this Magic Harp, with the draw notes on top in blue. (Why draw notes on top? Because they’re the high notes in each hole.) The blow notes, the low notes in each hole, are below in yellow.

The scale this harmonica plays is C D E G A – the C major pentatonic (five note) scale. Or it could be called the A minor pentatonic scale. The only difference is which note you use as the tonal center.

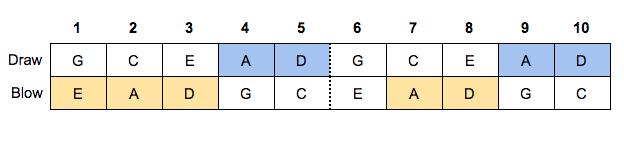

A C major chord consists of the notes C, E, and G, and you can find that chord (or fragments of it) in several places on the harmonica, as shown in the white cells here:

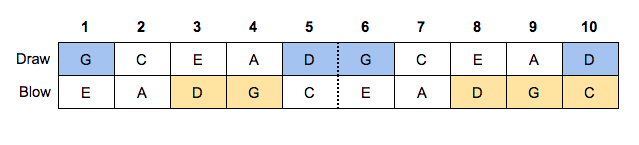

An A minor chord consists of the notes A, C, and E. This chord also occurs at several places in the note layout, as shown in the white cells here:

But in both cases, the chords have other notes both above and below that are not part of the basic chord. When you add those notes to the chord, they add new colors, sometimes sounding pretty, sometimes giving a floating feeling, and sometimes sounding dissonant. Why are the notes arranged that way? There are two answers.

The first answer lies in the fact that the pentatonic scale has an uneven number of notes – only five, not four or six, while blow-draw pairs of reeds create a structure based on even numbers. There are three ways to deal with this mismatch of even and uneven:

- Duplicate one of the scale notes, such as C, to create an even number. Chromatic harmonicas do exactly that, and so do some of the Magic Harp layouts. But not this one.

- Have two scale notes in a row in the same breath direction, like having both A and B as draw 6 and 7 on a standard C diatonic. But that would result in flipping the tuning over at that point, so that the following blow notes are higher instead of lower, like in Hole 7-10 on a standard diatonic. But that goes against the Magic Harp principle of always having the draw note in each hole higher than the blow note.

- Simply let the notes flow, as this layout does. This creates two interesting characteristics, though: spiral tuning, and chords in fourths, which I’ll discuss further below.

The second answer lies in letting the notes flow. if you take the notes of the C Major pentatonic and arrange them so that each successive note is four notes higher in the scale (taking your starting note and then counting up 1, 2, 3, 4) then you arrive at this sequence:

E A D G C

And that’s the arrangement of the blow notes on this harp.

If you take the same sequence but start it on G:

G C E A D

You get the draw notes on this harp.

And together, they give you the full pentatonic scale, arranged to that the draw note in any given hole is always higher than the blow note.

Chords in stacked fourths

The chordal byproduct of this note layout is that you get chords of stacked fourths (notes four steps apart in the scale) instead of the thirds that are used to create basic chords such as C E G (the C major triad, or basic chord of three notes) and A C E (the basic A minor triad). Chords in fourths are a staple of jazz piano starting in the mid-1950s, but it’s very unusual for a harmonica to be tuned that way.

Chords voiced in fourths tend to always sound unsettled, because they don’t give you all the notes of a basic triad at the same time. This harp gives you both the triad if you want it, and the unsettled, shifting stack of fourths with its color notes and dissonances.

But hold on, what about spiral tuning?

Spiral tuning

A spiral harmonica note layout (or tuning) is one where any given note in the scale is, say, a blow note in the first octave, a draw note in the second, a blow note again in the third, and so on – every note in the scale keeps flipping breath direction in each octave. And yes, the mismatch between even-numbered blow-draw pairs and an uneven number of scale notes – whether the five notes of a pentatonic scale or the seven notes of a major or minor scale – will naturally produce a spiral tuning, unless you introduce either a duplicated note or two successive scale notes on the same breath direction.

Making things pretty weird overall

Does spiral tuning make this note layout kind of slippery? Sure it does. Do the chords in stacked fourths make it sound untethered? Yes again. But that’s why I love this harp. And I hope that the recorded results demonstrate the value of that.

Hearing the other Magic Harps

Here are the Facebook Live videos I made to demonstrate the other four Magic Harps and offer them for sale (and yes, all were sold).

Magic Harp No. 1:

Magic Harp No. 2:

Magic Harp No. 3:

Magic Harp No. 4: